When Ouray’s new wastewater treatment plant is working, no one seems to notice.

The electrical panels, motors, pumps and other equipment inside the nondescript, earth-toned building at the northern entrance to the city hum along as they’re supposed to, under the radar. But when something goes awry — or multiple things, lately — everybody knows.

For several weeks, the smell of sewage hung thick outside the Panoramic Heights subdivision, a cluster of homes perched on a shelf on the outskirts of the city, where residents balance million-dollar views of Mount Abram with living directly above Ouray’s new $17 million mechanical plant.

When it stinks, resident John Pulbratek can’t enjoy a mug of coffee on his deck in the morning.

He keeps his windows sealed shut, trying to keep the smell out.

“I gotta live with it every day it’s there,” he lamented during a Ouray City Council meeting last month. “I can’t leave my windows open at night to get fresh air because I’m getting sewer air.”

Drivers passing by the “Welcome to Ouray” sign next to the plant were hit with stench stinging their nostrils, and the complaints rolled in.

Less than a year after coming online, the plant has been plagued by multiple mechanical failures. City officials believe they have fixed the root problems which led to the odors that have over- whelmed residents of Panoramic Heights, Whispering Pines and other nearby neighborhoods.

It’s one thing to make the fixes at the plant. But the biological process involved in treating wastewater takes time to recover, even after plant operators make mechanical or electrical adjustments. That means it can take days or weeks for the smells to mellow out.

Public Works Director Joe Coleman apologized during last month’s council meeting, telling residents he understands their concerns. He blamed a mixture of growing pains, learning curves and equipment malfunctions city officials are seeking to pin on the general contractor and subcontractors who worked on the plant.

“We are working on it as best we can,” he said.

The city’s new sewer treatment plant, located at the entrance to the city. Erin McIntyre – Ouray County Plaindealer

The sewer plant has been years in the making. The city’s old lagoon system was overtaxed and struggled to keep up with demand, forcing the city to restrict development in the last few years. Ouray exceeded the limits of its state wastewater discharge permit dozens of times between 2015 and 2019. City leaders initially considered retrofitting the lagoons but concluded it wasn’t a viable option and instead shifted toward a mechanical treatment plant.

The city hired engineering firm JVA initially as a consultant, then ultimately as the designer of the plant. It instituted multiple rate increases to help pay for the new plant and create more favorable loan terms.

When cost overruns plagued the project in 2022, the city switched at the 11th hour from Moltz Construction to Aslan Construction as the construction manager atrisk for the project. It worked with JVA to redesign the plant and trim roughly $3 million off the price tag.

The city began treating wastewater at the new plant in October. *** The task of turning hundreds of thousands of gallons of raw sewage and stormwater entering the plant every day into something that can be safely discharged into the Uncompahgre River relies on a combination of physical and biological processes.

The first step is a screening process to pull out solid items like toilet paper, rocks and sand. Fine particles like grit can cause the most damage to pumps used to treat sewage.

From there, wastewater is channeled through a series of tanks and basins containing a sea of plastic, perforated discs called “media,” which look similar to wagon wheel pasta. These wheels serve as the home for microscopic organisms that play a vital role in consuming organic matter, providing more surface area for them to live on in the tanks of sewage.

These small, plastic discs serve as habitat for microorganisms living in the sewer plant’s tanks. The right balance of conditions, including temperature, pH and oxygen levels, help the microorganisms live and digest the waste in the sewage. Erin McIntyre – Ouray County Plaindealer

Plant operators constantly monitor oxygen, temperature and pH levels to ensure an optimal environment for the bacteria, which are invisible inhabitants of these churning, bubbling vessels.

Coleman and Public Works Foreman Cliff Jaramillo call the microorganisms “bugs” that need certain conditions to keep them happy and doing their job. The plant relies on these microorganisms to break down the waste naturally, and making sure they have a healthy population of these microorganisms is vital for the system to work.

When the plant breaks down, or processes that affect the environment for the microorganisms aren’t working, things start to get smellier. That means if the electricity isn’t working or the tanks of sewage getting treated don’t have the right amount of oxygen because the pumps aren’t working, the balance of “good bugs” in the tanks gets disrupted. Other microorganisms start to take over, and it can result in the production of gases like methane and hydrogen sulfide, one of the culprits of the rotten egg smell.

An assortment of pumps and scrapers further separate solid materials from water. The end result is a treated, digested product known as biosolids that are funneled into a Dumpster outside the plant and emptied every four to six weeks.

***

Ouray’s public works staff first noticed malfunctions at the plant in May, seven months after it came online.

Water infiltrated an electrical unit for one of the pumps. It’s being rebuilt in Grand Junction and should be back up and running soon, according to Coleman.

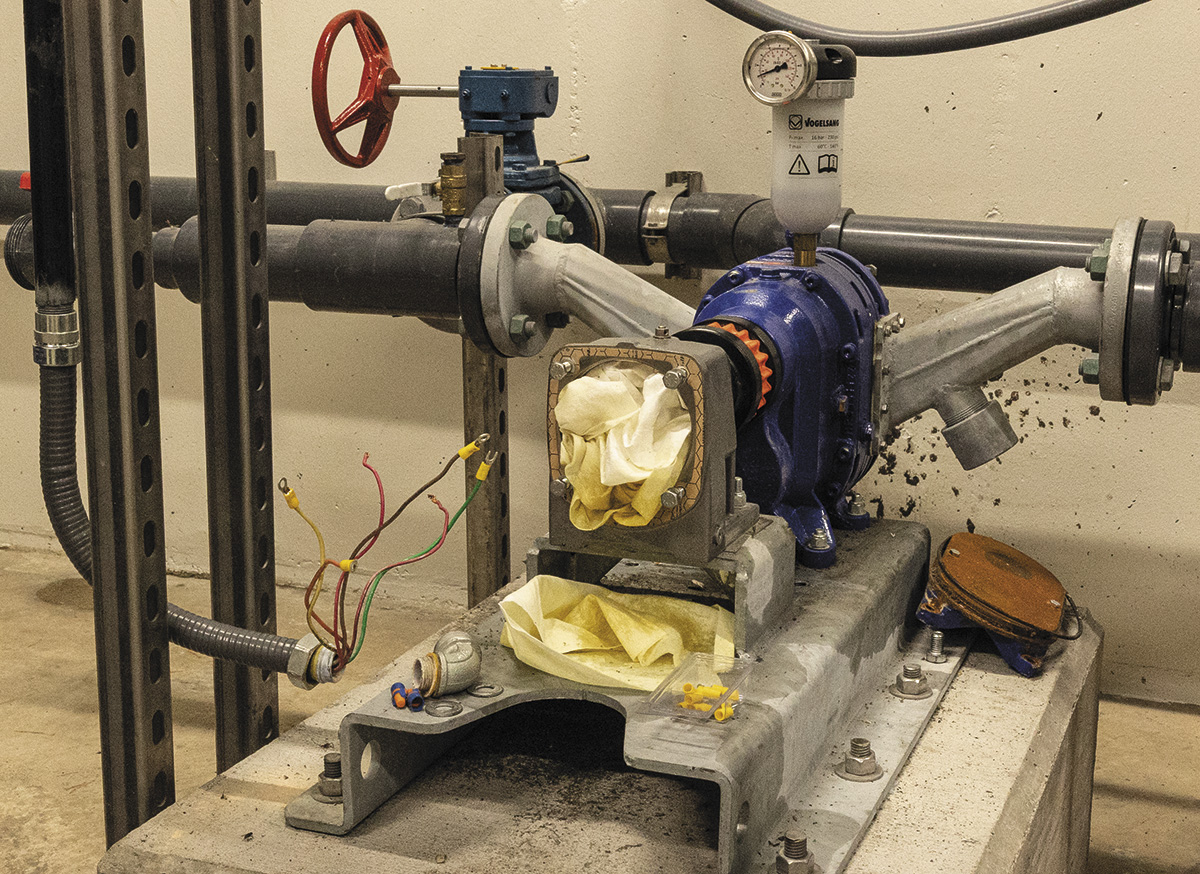

Two pumps that make up a redundant system to separate solid materials from water have both failed, with one breaking down twice. One of the pumps is working again, but city officials don’t know when the second pump will be fixed.

One of the broken pumps at the city’s new sewer treatment plant. Erin McIntyre – Ouray County Plaindealer

The breakdown that Coleman believes is the primary cause of the odor problems occurred at the end of June, when an electrical and communications panel that controls a series of pumps and blowers malfunctioned. That caused the environment in the sewage treatment tanks to lose the oxygen the “good bugs” need, and the system became anaerobic, triggering the stomach- turning smells that have plagued residents near the plant.

Plant operators didn’t discover the problem until after the Fourth of July. It took about a week to repair.

But, as Coleman noted during a meeting last month, “It’s a biological process. You don’t just turn a switch and suddenly it changes.”

It takes time for the bacteria to recover and to re-establish the proper balance of oxygen and nutrients that allows them to thrive and do their job. That’s why residents have continued to notice and report the odors that persisted into August.

The odors have been strong enough to provoke multiple complaints to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment’s Air Pollution Control Division. An inspector visited the plant and conducted an offsite odor observation on July 10 and found the plant was in compliance, according to Leah Schleifer, a spokesperson for the state health department.

She said the Air Quality Control Division had not received any more odor complaints as of July 28.

During a city council meeting last week, Councilor Tamara Gulde said she recently met with a couple of Panoramic Heights residents at their homes and noticed the same odors. She asked residents to continue to report their observations to the city, including the time of day odors are occurring and any variations in smell. She said that information can help plant operators identify sources of the odors and potential fixes.

Ouray City Administrator Michelle Metteer discusses the city’s efforts to solve problems at the city’s new wastewater treatment plant while standing inside the plant’s motor control room. The city has wrestled with a variety of electrical and mechanical failures since the $17 million plant came online in October. Photo by Erin McIntyre | Ouray County Plaindealer

City officials have had multiple conversations with representatives from JVA and Aslan to try to get to the bottom of the problems at the plant.

Coleman and Mayor Ethan Funk said the city’s primary focus is fixing the problems first, then sorting through warranty and legal questions later.

“There’s a lot of finger pointing going on,” Coleman said. “Rather than wait around and figure that out … it could take a significant amount of time, we want to get everything fixed and then we’ll figure those things out.”

That means money for repairs is currently coming out of the city’s own pocket. Coleman said one of the pumps that failed will cost $2,000 to $2,500 to rebuild. He didn’t have estimates for additional expenses.

The plant is under an assortment of warranties. Equipment is guaranteed for a year in some cases, two years in others, according to Coleman. Some of the warranties are based on the purchase date, while others apply to the installation date.

The warranty for the building itself lasts for two years, and it applies to facility construction and materials, Aslan owner Mike Pelphrey told the Plaindealer. Failures related to the design or operation of the plant fall outside Aslan’s warranty, he said.

There are some breakdowns that fall under Aslan’s warranty, Pelphrey said, and those “are being addressed.” But there are other problems he believes don’t relate to the work Aslan performed. He didn’t cite specific examples in either case.

He estimated Aslan has conducted six to eight warranty investigations.

“We’re absolutely willing to take care of any normal warranty issues,” Pelphrey said. “And we’re willing to be a participant in investigating these things. But it takes more than just us participating.”

A representative from JVA did not respond to a request for comment by Wednesday.